TALES

16-02-2021 by Marco "Sbringo" Bigi

Shella, pronounced Scèla, is an old quarter of Malindi in which, among the thousands of influences imposed by the various rulers, coming from the most disparate places, and who have alternated over the centuries, it is the Arab influence that still makes itself felt today, as indeed has happened on much of the African and Asian coasts bordering the Indian Ocean.

Because of the labyrinth of alleys in which it is easy to get lost, it is rare for a tourist to enter the maze of Malindi.

I myself had never been there before the Sappe dragged me there to go and eat pojo e sima (lentils and polenta) at Mansur's little restaurant, thus allowing me to catch a glimpse of a maze of narrow streets, past low houses, old men sitting on patios watching people go by, women preparing food outside on lit embers, while hordes of children run around festively and the voices of the Muezzin are heard at precise hours from the loudspeakers of the numerous mosques.

The luxury of the houses, almost all of which have only one floor, is evidently proportional to the income of the owners, which is on average very low, since inlaid doors and typical pointed arches are rare, while sheet metal roofs and peeling walls of houses inhabited with great dignity are much more frequent.

Walking around Shella, there is no danger at all, on the contrary, big smiles, greetings, a lot of curiosity, a few words in English from the younger people who have studied and the inevitable "ciao", which is now part of the local language, almost as much as the famous "jambo". More reserved are obviously the women who, from under their veils, limit themselves to casting glances at strangers that last only the blink of an eye and seem to penetrate you like the rays of an X-ray.

Following the instructions given to me by the Sappe, I parked the Pajero in the nameless square overlooked by the fire station and walked, with my bag over my shoulder, into the so-called Shella Road, at that time unpaved but now finally paved, which leads to the sea.

"Go on for about two hundred metres and then turn left into a small courtyard. If you see a yellow two-storey building at the end of it, that's where you need to go," he told me on the phone.

I reached the courtyard and was startled by the sight of a dilapidated house that, as dilapidated as it was, brought to mind news images of a bombed-out Beirut in its worst days. The encrusted walls revealed, under the last coat of yellow, geological eras of red and blue paint, even some prehistoric patches of green and purple revealed brushstrokes of ancient painters. Probably drunken or simply incompetent masons had carried out half-finished works, such as a concrete beam about three metres high, sticking out a little crookedly from the base of a small terrace and disappearing into thin air. In the small hallway, a huge wooden board hung, nailed to the wall somehow, almost collapsing under the weight of several electricity meters surrounded by tangles of electrical wires. A barred door revealed the presence of a ground-floor flat, and to the right an alleyway opened up, leading to another unexpected courtyard, from which a curious goat and an unusually squawking hen appeared. Finally, a side staircase with very irregular steps climbed up to the left, and it was there that Sappe had told me to go to join him in his "palace" upstairs.

I found myself in front of a black iron door in which there was a hole, big enough for a hand to pass through, that allowed a glimpse of a padlock hanging from the inside. Ingenious system, I thought, to use just one.

I knocked and heard the muffled voice of the Sappe shouting at me: "Just a moment, I'm coming!"

The branches of a tree, full of yellow flowers, shaded the landing on which I was standing, and while I waited for the Sappe to come and open the door, I was struck by the neighbouring building, in pure Arabian style, which seemed to come straight out of a story from the Arabian Nights.

From this height I could see the small courtyard, where an old man in a white tunic was sitting cross-legged on a step drinking tea.

As the Sappe fiddled with the lock, the Baba looked up at me and waved, to which I replied with a smile.

With a loud "Caclack" the door opened and the Sappe gave me the classic Swahili welcome: "Karibu Rafiki!"

A corridor with a light bulb dangling from the ceiling led, on the right, to the small terrace with the hollow beam I had seen from the courtyard, from where another staircase probably led to the terrace above. On the left, there was a balcony with five or six doors. That view was very reminiscent of the railing houses of old Milan sung about by Enzo Jannacci and Nanni Svampa.

Sappe went to the right, towards the only door in that direction and beckoned me to follow him, saying: 'This is my kingdom'.

I entered, looked around and burst out laughing, "But this, haha, is a caravan!"

It was a tiny studio apartment with minimal furniture. Under the window there was a foldaway table, under which I could see some wooden stools that also had the function of supporting one of the two mattresses resting on a sofa that, thanks to this artifice, turned into a bed.

At the far left was the kitchenette with a sink and brickwork shelves on which an electric cooker was placed. To the right I saw a bookcase bent by the weight of countless books and finally, a door led into a small bathroom with a shower.

A fan moved the air from the ceiling and from the window I could see all the roofs of Shella as far as the sea. Compared to the dilapidated exterior, the first thing that jumped out at you (and if you wanted to, your nose as well) was the cleanliness: spotless walls, not a speck of dust, washed dishes neatly arranged on the dish rack, the coloured sarong covering the sofa was ironed and you could see all the clothes neatly arranged in the wardrobe made out of a recess in the wall. On the walls hung some paintings that I recognised as his, from some sketches he had scribbled on napkins in the bar (also a painter, I thought).

Between the narrow spaces left free by the sofa and the table, the Sappe, who moved as gracefully as a dancer, went towards the kitchen corner asking me "What do you drink? Coffee? Tea? Or beer?"

Without waiting for an answer, he opened a small fridge that I hadn't noticed, the kind you'd find in a hotel room, and pulled out two bottles of Tusker, uncorked them and handed me one.

"It was a rhetorical question, so," I said, taking the beer, "but... (I paused theatrically) isn't it time to stop asking rhetorical questions?"

"Ahaha good one!" laughed Sappe.

"Rather,' I said in a more serious tone of voice, 'I see that, as you are teaching, your accommodation has no more than one room...'.

"Ah, you're worried about your accommodation? - he interrupted me - come with me!"

He stepped through the doorway, walked to the balcony with beer bottle in hand, opened the first door on the left and stepped back with an ironic reverence to let me through.

I entered and saw a perfect hotel room, with a bed surrounded by a mosquito net, a bedside table, a table, a chair, a wardrobe and a sink in the corner. The sheets and towels smelled like laundry and even here a fan hung from the ceiling.

"At the end of the gallery there are two bathrooms with showers, one is for your exclusive use, the keys are on the bedside table. You can stay as long as you want, for the first week you are my guest, if you want to stay longer, you will pay me what I ask of my clients. A pittance for a Mzungu like you."

"But what is a hotel? Is it yours?"

I could tell from his expression that he was about to give me the umpteenth pearl of wisdom. With a solemn air, he said, "When you think you own something, that thing owns you!

He then continued in a normal tone: "This building used to be a Guest House and upstairs on the terrace there was a beautiful bar with a large makuti (thatched) roof. The roof burned down, the owner had a crisis and closed everything down. At that point I offered to let him manage it and here we are, the other rooms and the flat downstairs are occupied by good people who get up early every morning to go to work. I'd say the only ambiguous characters here,' he looked around and assumed a confidential tone, 'are you and me.

You just had to get used to the singing of the muezzin, the tuktuk warming up the engine under the window at six in the morning, the children's voices, the bleating of the goats and that damned rooster that started crowing many hours before dawn. Otherwise it was fine in the Sappe Guest House. Every day a shy girl came to do the cleaning and it was a chance to let her have her room and go for a walk.

I liked Shella and its people liked me.

Evidently the word had spread that I was a friend of the Sappe and everyone greeted me calling me by name, asking me how I was, if I needed anything not to make trouble. When I passed by, the children ran towards me joyfully and gradually I got to know the neighbours, such as George, who ran a spartan little restaurant, too full of flies to accept his invitation to sit down, or Mohammed, a guy who ran a plumbing shop who always gave me big smiles. I recognised Farid, the old man I had glimpsed on the first day from the top of the stairs, who told me about the recent death of his wife and who always insisted that I go and have tea with him, and finally Raphael, a lively little six-year-old boy who every time I arrived he got into my car, got behind the wheel and made "brum brum" with his mouth. There was no news of his mother," said Sappe, "and he and his brothers lived with their grandmother, who did her best to support them. Every now and then, he would give her a few shillings and make sure the boy went to school; it was his only hope of emancipating himself from the condition of a street kid.

I was so fascinated by the new experiences that for a few days I relaxed, forgetting the tensions of the previous weeks, until late one morning, while sitting at the bar with Sappe, I decided to try to call Ettore. The classic recorded voice warned me that the phone might be switched off or unreachable.

"That's strange, he's gone," I said to myself.

"Who are you talking about?" the Sappe asked me.

"Ettore.

He hasn't disappeared," he replied, looking at his watch, "he's probably flying over Somalia towards Rome by now.

"But how, he's gone? Without telling me anything? And how come you didn't tell me anything?"

"Because he had become your obsession, you see how good it did you to change air..."

"Yes, I thank you for that, but... let me understand, he left without saying goodbye, that means he ran away, what did Makotsi do to him? Did he pretend to be a ghost and tickle his feet in bed?"

"Nothing like that, he simply stayed at your place with his wife and children."

"I still don't understand, it doesn't seem that simple to me - I stayed for a moment thinking and then asked - how many children?"

"I don't really remember, definitely eight, maybe nine, all I know is that the oldest, Adam, is a fourteen year old because I was his godfather then I lost count. The others, of course, will be between zero and thirteen," replied the Sappe, looking me in the eye to study my reaction.

My laughter immediately burst out, "Ahahah, eight or nine brats in the house, crying, running, screaming, playing... I understood why Ettore ran away, you're a genius, my friend!

It was the right occasion to order some sparkling wine.

When the waiter brought the bottle, I poured and raised my glass: "To the departure of the uninvited guest!"

"Cheers!"

We tasted the precious nectar, rare in these parts, and then I said: "Now I can finally take possession of my house again."

"I don't think so," intervened the Sappe.

"Why?" I asked with a worried air.

"I don't think it's easy to get Makotsi and his family out of your house at this point, he told me he's very comfortable there."

I couldn't retort as I would have liked, "But... how... what?"

"And then, I mean, we had decided to take care of Hector first, and we managed to send him away...first the spider. then the wasp, remember? Come on, finish your wine, we're going back to Shella!"

(...continue?)

PLACES

by redazione

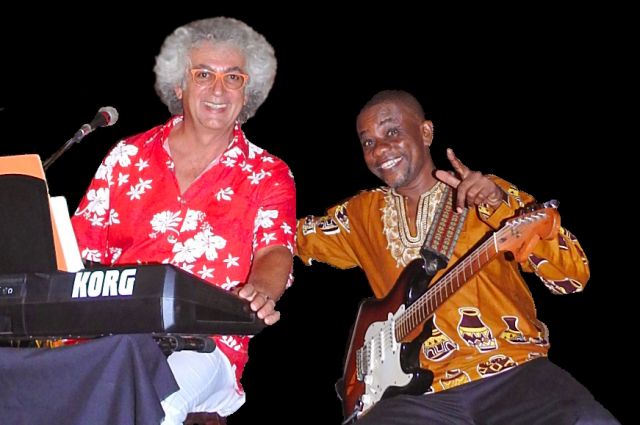

After the success of the Italian-Kenyan evening with the excellent guitarist Ray Seed (compliments to Sbringo Master for dredging this up), continuing Thursday in Music Baby Marrow.

EVENTI

by redazione

One last show to close the season and to hand over to the Italian non-profit organisation Karibuni the fruits...

Another night for Freddie and Sbringo and their lucky show between songs and stories "Once ...

Places

by redazione

Weekly appointment with the Italian aperidinner in the beautiful resort and restaurant...