TALES

03-04-2021 by Freddie del Curatolo

In 1998, the writer and sociologist Spencer Johnson published a booklet that quickly became a best seller among those who felt the burden but also the opportunities for improvement of the social changes taking place and to come in the early years of the New Millennium.

The book is entitled "Who Moved My Cheese?" and tells a story that is a great metaphor for mankind these days.

Those who frequent Kenya and know it, know that such a story could easily be set in the African country and, at a time when there is time to read and reflect, having to stay at home, we gladly offer you an adapted summary, referring of course also to the reading of Johnson's original work.

Two homeless labourers from the outskirts of Malindi, Fondo and Kahaso, work temporarily in a corn meal warehouse, the kind used for ugali, the Kenyan national dish. In the building with its many rooms and doors that divide up the stocks and then allocate them to all the trucks that come to load them and take them to every corner of the county, the askari Gunga and Gongo also work.

Every day the labourers arrive, help with the loading and then stay around, because there is always a pile of flour lying in some room that has escaped from a broken packet or even a package forgotten in a corner.

The owners of the depot let them, as long as their employees are careful in their work. They know very well that behind the depot there is a pot and charcoal always ready to prepare big plates of ugali with sukuma wiki or mchicha collected from a nearby garden.

Sometimes, in addition to the daily ration, there is also something to be salvaged for the family or simply to sell for a living.

Kahaso, known as Big Nose, has now learnt to sniff out a speck of "unga wa mahindi" even at a distance of fifty metres, while Fondo, known as "Girotondo", could be a speleologist as he is so good at discovering niches and hiding places.

So, thanks to the complicity of the two askari, every evening they expertly inspect the structure in every nook and cranny and always find something. They wander about with circumspection, ready to run away and even lose their jobs and have to emigrate somewhere else to collect food if they are discovered.

The askaris, on the other hand, are more relaxed, have a fixed salary and sometimes arrive slightly late, because they know that there is food somewhere for them too.

One day, due to an unexpected pandemic, the crisis arrived in Malindi and flour became scarce.

The first to realise this are the two labourers, who take their few belongings and change town, looking for other warehouses, granaries or companies that produce something.

In short, the situation had changed and they changed with it.

The askaris don't take any notice at first, they come to work with their usual phlegm and then start to get indignant.

"It is an injustice, this job is now too unpaid and more tiring" they say.

They had built up a fairly comfortable life for themselves, compared to other categories who had to fight every day for their share of the "equality".

The next day they arrive a little earlier, inspect the rooms and don't find a single package of flour, but at the same time realise that Fondo and Kahaso have left.

Could they have taken all the flour with them? Impossible, they probably went to look for more elsewhere. But how come there's no flour left in this storehouse, who took the ugali away?

Gongo, who is always laughing even though he has only one tooth and a wobbly one at that, suggests to Gunga, who passes for being chronically indecisive, that he should quit that underpaid job and go in search of Fondo and Kahaso or at least some additional food.

Gunga flatly refuses, preferring to wait and not give up what little security he still has left.

Every morning Gongo, who doesn't have the courage to try on his own, tries to convince Gunga, but always gets a flat refusal.

In the meantime, Girotondo and Big Nose have found another temporary job that allows them to earn some extra money. They work in a cashew nut factory in Kilifi and manage to make ends meet, perhaps even better than before. It took them a while to gain the credibility of the owner who initially underpaid them, but now they always manage to come out with full hands from the factory where they pack thousands of nuts a day.

For Gongo and Gunga, on the other hand, the stress increases every day and they come to complain as if the 'good times' were an assimilated right and not a temporary fluke.

One night Gongo has a dream: he sees the two labourers who are doing well, have a big belly and are enjoying a bottle of beer at the pub. So he wakes up and imagines he can reach them, wherever they are, and get hired as an askari, or even as a worker, why not?

Gunga starts to waver, but he wants to wait until the end of the month, he is convinced that something will come along and that if they put their minds to it they will sooner or later manage to find some generous legacies.

"I'm too old to start looking for another job, I'd be a fool to leave this one to go on an adventure at this time."

Gongo starts to giggle as he does when he's thinking, touches his wobbly tooth and jumps. He laughs even harder thinking that in the end it is only fear that keeps him from acting.

So he takes a lump of coal and writes on the wall of the flour store: "What would you do if you were not a fearful man?".

He decides to answer his own question, taking a deep breath and hurling himself towards an uncertain future. As he sets off, he realises that this period of little food and many thoughts has weakened him a little, and he swears to himself that if he has to face any more changes in life, he will not be so unprepared in the future, but will play it by ear, following reason without forgetting instinct.

The giggling askari wanders around the county for days and nights in search of a plate of ugali and any job, but it is not easy. The strength that sustains him is the thought that lying down to check an empty warehouse would not have changed anything: at least on the way he meets people, exchanges opinions and smiles, learns something. He finally feels in control of himself and his situation, he doesn't wait for gifts from heaven or complain if they don't arrive, but is more attentive, receptive.

Every now and then he thinks back to his friend Gunga and wonders whether he too has moved or remained in the warehouse, paralysed by his fears.

He doesn't know how this story will end, whether one day someone will find him exhausted and debilitated on the threshold of a hut or whether he will be transported by some witch doctor who will make him drink moringa decoctions.

He has made a habit of leaving marks of his passage on the outer walls of the brick buildings he comes across on his way. With his piece of charcoal he writes "When you move beyond your fears, you feel free". It is the power of imagination that keeps him on his feet. When he dreams, he imagines his new job, thanks to which he will be able to enjoy a big plate of ugali and stewed cabbage, his favourite condiment.

On another wall he writes: "Imagining that I will enjoy a new plate of polenta, even before I have found it, leads me to it".

And when, in a village on the way to Kilifi, he finds another almost abandoned flour depot, he is disheartened, even though he manages to use his experience to recover a few piles to boil outside a hut with the help of a generous mama.

He hastens to make a note on the side of another building: "The faster you leave the old nozzle, the faster you will find the new one".

That's right. Gongo is now happy not only for the daily ugali, but for the feeling of not being a slave to fear. He feels stronger and safer than when he was working without wondering about the future, in the Malindi warehouse. He writes: "It is safer to look around than to stay in a situation without ugali".

He also understands that the fear in his own mind was harder than the reality: "Old beliefs do not lead you to new ugali".

And finally it happens.

Gongo stands in front of the cashew factory that is doing great, thanks to a contract with an American multinational. There he sees Kahaso Grande Naso and Fondo Girotondo who are no longer simple workers, but have a quality control manager's uniform and a big belly.

Next to the factory is a canteen that prepares more than two thousand plates of ugali every day for the employees of the factory and other companies in the Kilifi industrial district.

"Do you think they could hire me as an askari?"

With the contract in hand, Gongo therefore understands three things:

1. The greatest obstacle to change is within ourselves

2. Things don't get better if you don't change yourself

3. There is always a new plate of food out there for you, believe it or not.

It would be easy now to fall back into laziness, but he knows that he will not fall back into the old mistake.

Even though he has a sumptuous plate of ugali a day with his job, plus a salary to send to his family, he won't let too much time go by without checking that no one is taking away the flour reserves and if he has to turn a blind eye, it will be for someone in whom he sees his own spirit, or that of Kahaso and Fondo . Never take anything for granted, but be ready for a new change. During one of his nightly patrols outside the canteen store, he hears a noise, as if someone is approaching. For a moment he hopes and prays that it is his friend Gunga, and that he too has learnt the lesson "Move with the ugali and appreciate it!".

A good read, about past times and those who dream of reviving them, until reaching the origin of those ancient tales narrated here. It's the Kenya of «Lord of the prairie», the latest book by the spanish writer Javier Yanes.

EVENTS

by redazione

This year Freddie of the Curatolo chose children as a public to tell her stories of Kenya, between nature, solidarity and fun moments.

They are elementary schools, especially quarters and scenes, listening to stories that go from baobab to schools...

EVENTS

by Leni Frau

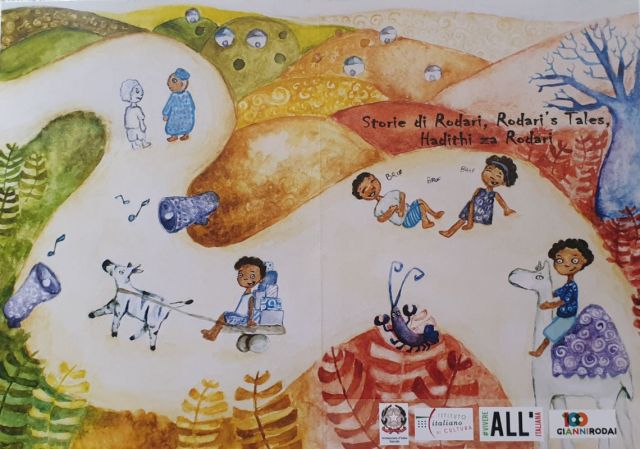

The children's fairy tales of the unforgettable Italian writer and educator Gianni Rodari, land in...

EVENTS

by redazione

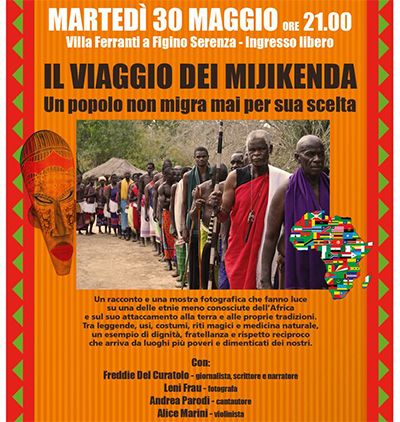

An evening of stories about Kenya and the Mijikenda ethnicity this Tuesday at Figino Serenza in the province of Como.

With free entrance, in the beautiful and elegant frame of Villa Ferranti, the headquarters of the municipal library, Malindikenya.net's director...

BOOKS AND STORIES

by Freddie del Curatolo

"Life goes on, and with it the tenacity of the reporter. And that is why I wanted to remember...

DOCUMENTARY

by redazione

The filming of the documentary film "Italian in Kenya" has ended. It's a short feature commissioned by the Italian Foreign Ministry, through the Italian Institute of Culture in Nairobi, as part of the week of Italian language in the world.